Intimacy v Interwebz

Intimacy v Interwebz

by Taylor Mazza

Before the Internet graced the desks—and then the laps, and the palms—of the general public, “intimacy” was a fairly straightforward term. The level of closeness between the constituents of any given twosome was formerly measured in terms of “the level of commitment and positive affective, and the physical and cognitive closeness one experiences with a partner.” (Moss 33)

It seems as if even when the constituents are among the heaviest of technology users, this traditional sort of intimacy is still present. If technology is the medium through which two people achieve and maintain, say, cognitive closeness, is said closeness discounted? I cannot not see why it would be. Especially because when one picks apart the components of the term and spreads them out on the table, the term, even in the traditional sense, is still applicable to relationships between wired-in individuals.

Some definitions of the term read: 1) An exchange or mutual interaction 2-4) The reception or expression of affect, physical acts, and cognitive material from and to another 3) The reception or expression of cognitive material from and to another 4) The reception or expression of physical acts from or towards another, ranging from inter-personal distance to sexuality 5) A shared commitment and feeling of cohesion 6) Disclosing or communicating information from any content domain to another 7) A generalized sense of closeness to another. (Moss 33)

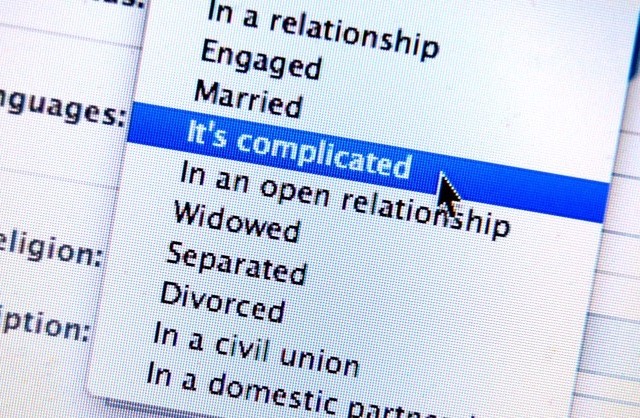

But there are many who disagree, such as Towson University professor, Andrew Reiner. In his article Looking for Intimacy in the Age of Facebook he argues that technology has completely destroyed the construct that is intimacy. He explains that while intimacy achieved via technology may not be any less than that achieved in the absence of technology, the likelihood of achieving intimacy is markedly slimmer. So, while one can reach traditional intimacy, it is likely that one will have to settle for a lesser and/or warped version of the construct.

Reiner made this ridiculously apparent when he challenged his students to speak of their true feelings with someone they are close with: “‘It has to be a text that shares your true feelings about something this friend has done or said that upset you but that you never said anything about. Say what you mean and hit ‘send.’” (Reiner)

The responses he received from his students borderlined, and in some cases, reached hate: “‘I’m really hating you right now,’ one student murmured.” (Reiner) How fearful they were to speak honestly with a friend! If we are not even comfortable communicating honestly with those we care about, how can we claim to be intimate with them?

Definition 6 of intimacy: “Disclosing or communicating information from any content domain to another” seems absolutely absent from modern relationships, romantic or otherwise. (Moss 33)

Stefana Broadbent, a professor at University College London, stands opposite Reiner in her TED talk How the Internet Enables Intimacy. Her argument is that technology makes our loved ones ubiquitous in a way. Regardless of whether or not we are physically near them, we have the ability to be with them at all times (Broadbent). We can receive and express of cognitive material with them, we can share and disclose information with them.

At all times.

As a result of the emergence of technology, we have endless opportunities to create and maintain intimacy. In fact, the description for Broadbent’s talk reads: “Stefana Broadbent‘s research shows how communication tech is capable of cultivating deeper relationships.”

I contend that the key word here is capable. The couples she spoke about harnessed that capability to create intimacy. However, I find her findings to be one-sided; she only tells of the times in which a couple is apart and thus use technology to stay in touch.

But what happens when the couple is together? Are they using technology to keep in touch with others? Is their use of technology while apart the extent of their intimacy? Does technology leave their intimacy floating in cyberspace? But, who is to say? I entertain the notion that technology can be used to construct intimacy, but, as Reiner’s class showed us, albeit slightly shamefully; it is not often that we use the technology at our disposal for such purposes.

David Wygant of the Huffington Post brings us back, or at least tries to, into Reiner’s corner with his article, “How Do the Internet and Intimacy Relate?” He brings up a hazard of the “intimacy-killer”—a.k.a. the Internet—that we cannot necessarily defend ourselves against: Its addictive quality.

Professor Katherine Herlein of the University of Nevada explores the psychological effects of the addicting quality of the Internet. In her presentation, Couple and Family Technology: The Emergence of a New Discipline, she includes a statistic that illustrates the way in which the cognition of Internet addicts are altered by their drug of choice. She cites that Internet users commonly think of their interaction with their in-the-flesh-partners as smothering. The Internet, then, has given us a perception of what we previously thought of as a normal, healthy interaction a negative spin. What were previously intimate, personal, possibly romantic, interpersonal relationships are now dodged as we become increasingly more comfortable behind our computer screens.

Herlein also reported that those who are in online relationships feel closer to one another as they were more inclined to disclose personal information while being protected by their computer screens.

To return to Reiner: “They edit, Photoshop and solicit the ‘right’ messages and photographs for their profiles with an obsession worthy of a lengthy research paper.” This eliminates any sort of vulnerability that would otherwise be present in relationships if social media had not entered them. You cannot be intimate with a contrived entity. If a given person is not open enough to share honestly on networks, then there is no vulnerability, and thus no intimacy.

Also, the computer-generated confidence online daters have is a transient asset. Once they log off, they lose their security blanket and essentially go into shock. Their confidence cannot transfer over into the real world so they near recluse. Online confidence eradicates what is left of the real-world confidence.

It seems, then, as if Wygant’s claim that Internet is an “intimacy-killer” is becoming less and less a radical statement, no?

A case study that I conducted proves it to be true. What is interesting, though, is not the data that I obtained (I asked if my subjects thought technology brought them closer together with their friends and family. 33 college-age kids responded “yes” while 27 responded “no”). The interesting part is the pains my friends and I had to go through to get this data.

Before I took to the streets with my notebook to poll people face-to-face, I used three of my friends’ Twitter accounts to see what data I could collect from there. Between the three tweets and the 822 followers between the accounts, we got zero responses! I contend that the Internet makes it all too easy to avoid interaction. The landscape of most social networking sites makes it ironically easy to be completely nonsocial.

As Clay Shirky, a media professor at NYU, points out, the Internet is very good at providing space for conversations, specifically, many-to-many conversations. However, the fact that my case study flopped on the Internet proves that the Internet does not necessarily facilitate conversation—it can, but it does not always do so. One’s words go out to no specific person and so no response is guaranteed, no audience is even guaranteed.

I watch my friends scroll passed what seems like a million tweets a day, not even glancing long enough to skim most of them until they see a tweet from someone they deem worthy of their eyes. They follow to be followed, the interaction is secondary.

I had very different experience when I took to collecting data face-to-face. It is much harder to ignore a five foot person standing in front of you, you are forced to engage, you cannot just scroll me away—we need to stop scrolling our social lives away.

Technology is a tool. It does not, on its own, create or destroy intimacy traditional or otherwise. Intimacy is and will remain to be, with or without the presence of technology, a human construct. It seems as if we are becoming less and less likely to use technology as a tool to construct intimacy. That is why I believe the numbers from the case study stacked the way they did: Intimacy is not dead, we are just killing it. The numbers say that more than half of us have already resolved to mourn the loss of intimacy, but alas some of us may have figured out how to properly use the tool.

Notes:

Broadbent, Stefana. “How the Internet Enables Intimacy.” Stefana Broadbent:. TED, July 2009. Web. 15 Apr. 2014.

Moss, Barry F., and Andrew I. Schwebel. “Defining Intimacy in Romantic Relationships.” Family Relations. 1st ed. Vol. 42. N.p.: National Council on Family Relations, 1993. 31-37. Print

Couple and Family Technology: The Emergence of a New Discipline. Nevada: University of Nevada, 21 Feb. 2013. PDF.

Reiner, Andrew. “Looking for Intimacy in the Age of Facebook.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 02 Nov. 2013. Web. 15 Apr. 2014.

Shirky, Clay. “How Social Media Can Make History.” Clay Shirky:. TED, June 2009. Web. 09 May 2014.

Wygant, David. “How Do the Internet and Intimacy Relate?” The Huffington Post. TheHuffingtonPost.com, 20 July 2010. Web. 15 Apr. 2014.